“Marking, as the name implies, is the art of putting some distinguishing sign or mark on body and household linen, so that it may not be lost, especially in the laundry. It is therefore necessary that all washing things are clearly and distinctly marked.”

Make a cross-stitch, taking the first diagonal stitch over two threads of the fabric, and then another for the other side of the X. Your letters and numbers must each be finished off separately and not connected by a thread on the back. They will be about seven X’s in height.

Depending on how fine your fabric is, that means your A, B, C or 1, 2, 3 might be (gulp) 3/8 of an inch tall! Yes, seven little stacked crosses making your initials only 3/8″ high. I think good eyes and a sunny window would help.

Is it any wonder that marking was considered painfully tedious? Any wonder that any alternative method of defending your linen was highly desirable?

As a student of plain work, I’m in awe of the blindingly tiny stitches that were used for marking. I’ve blogged about it some here and here. But anyone who studies plain sewing will notice that during the 19th century, a new solution was the solution: indelible ink!

Here’s a recipe (one of several) from The New Family Receipt-Book, 1811:

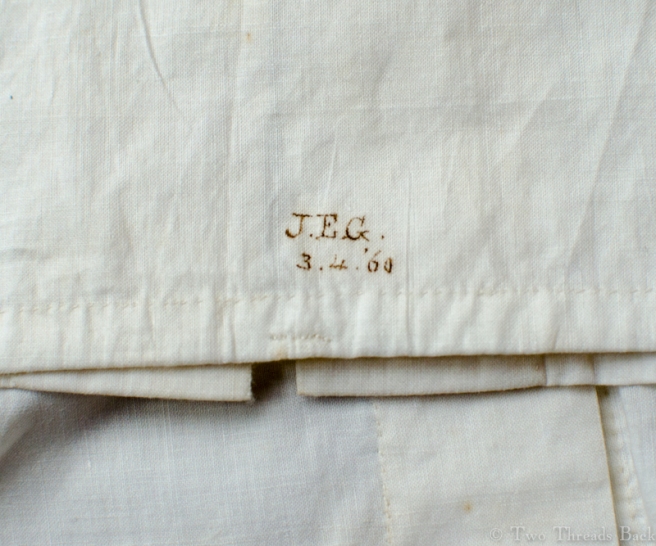

Apparently the new and easier way caught on quickly. By 1833, Lydia Maria Child states in The Girl’s Own Book, “Indelible ink is now so much in use, that the general habit of marking samplers is almost done away.” Letters marked with ink could be very neat and elegant, such as this example on a lady’s chemisette, dated 1860.

Or indelible ink could be somewhat … disappointing. Unlike stitches made with thread, you can’t pick out an uh-oh. Miss Colby probably cringed when she saw how this one turned out – an untidy finish to her corded stays.

But wait! As we move from marking with needle and thread to marking with pen and ink, we’re moving into the decades of innovation: those glorious years celebrated by Great Exhibitions and more new patents than you could shake a stick at. Wouldn’t it be nice to have your cloth held taut while you wrote? A cloth stretcher could handle that.

And if the ink got too messy, well, someone had an answer for that, too. An indelible marking pencil could solve all your linen identity crises. Housekeeper, is your “brain feeling considerably bothered” by directions for using ink? An indelible marking pencil can relieve it!

Indelible ink, cloth stretchers, and marking pencils weren’t the only advances on cross-stitch. Stencils were available from stationers or engravers, and could be had by mail order. Mr. Congdon of Worcester, Massachusetts offered such aids, as seen in his ad from 1856:

But would stencils work with small letters and numbers on linen? Fortunately, we have surviving examples to show that they worked quite well.

“Cena B. Barrett m. Hiram Hurlbut 3 Feb. 1862, West Hartford, CT.”

And if thread, ink, pencil, and stencil didn’t suit, along came another option: ready-made. The machine embroidered letters came on a length of tape. They even came in Traditional Turkey Red.

The pursuit of convenience was just as fervent in the 19th century as it is in ours today, but there have always been a few voices arguing the superiority of the old ways. They certainly kept marking in the needlework curriculum until the early 1900s. While requiring more skill and more time, marking with needle and thread rendered articles “ornamental, tidy, and finished.” I suppose the tiny marking stitches are the nicest way to make your mark – for all time!

Oh my goodness. Will read again and again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

If Hitty hadn’t had “five letters worked carefully in little red cross-stitch characters upon her chemise” we wouldn’t have known her name throughout her “First Hundred Years”.

I love laundry marks!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yet more fascinating history. I have a few bits of old linen, cross stitch marked or embroidered, and once again there is that connection with the original maker, a direct link to another time – with so many unanswered questions. A beautiful and intriguing post!

LikeLiked by 1 person