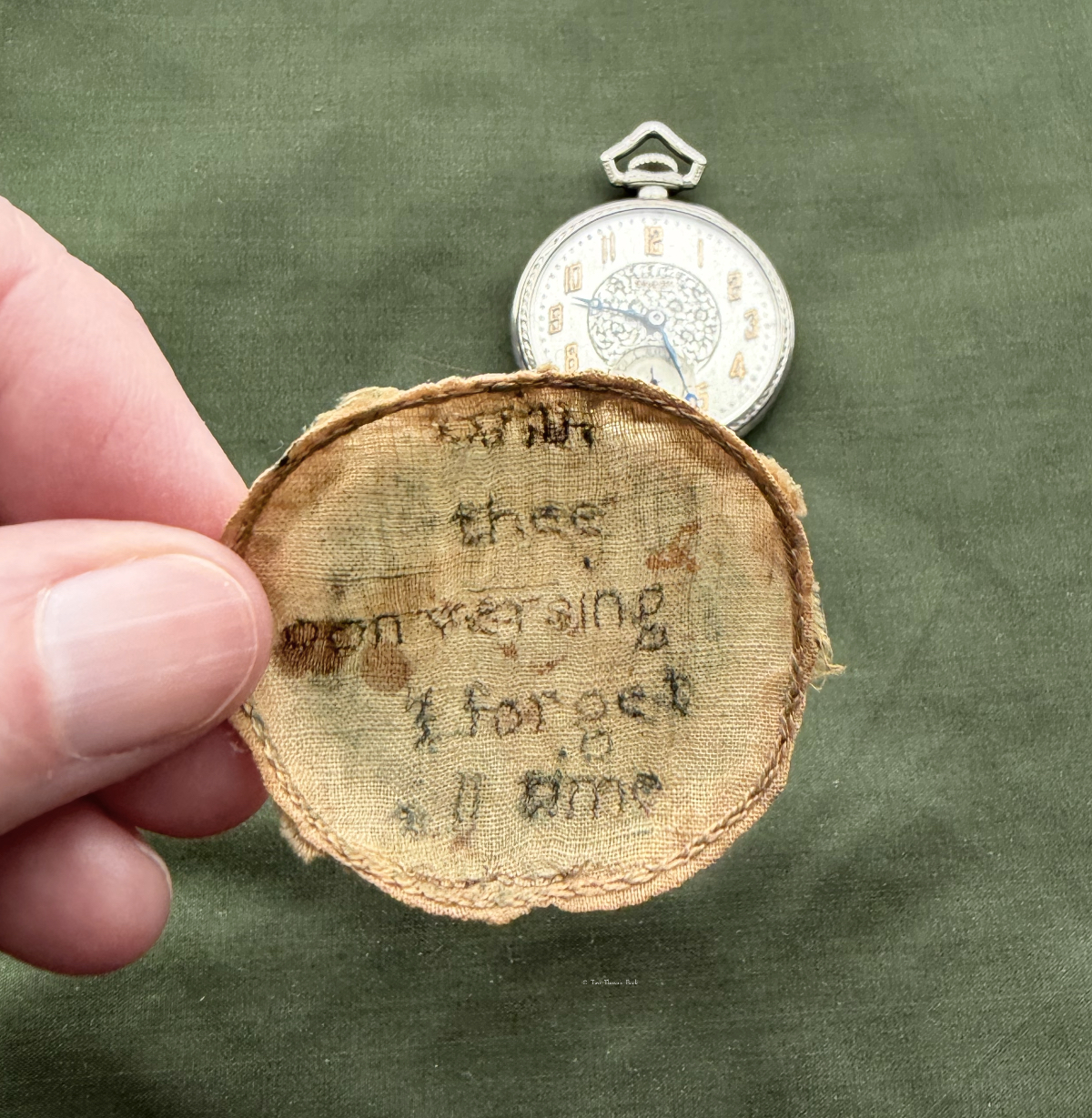

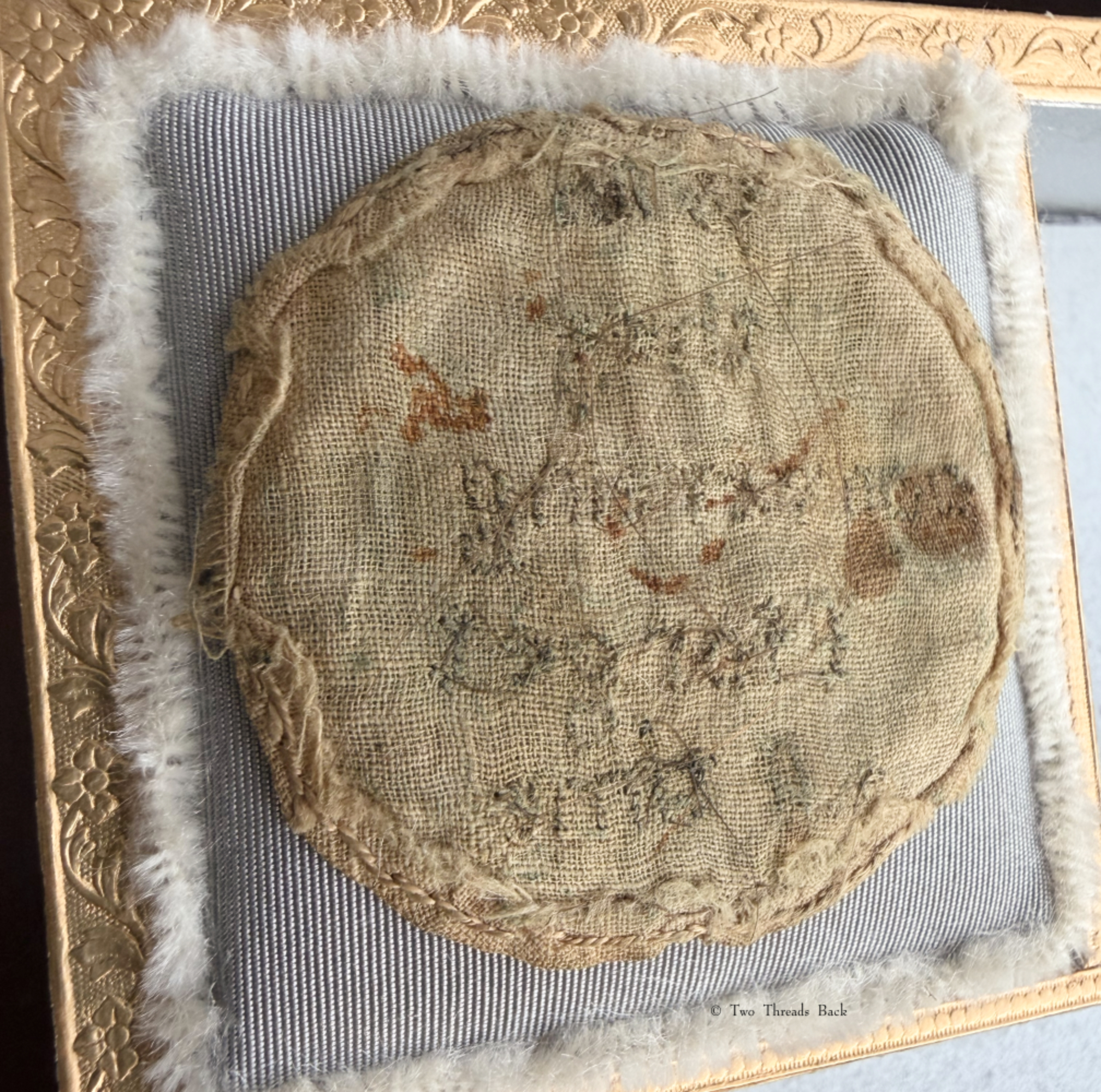

Plain sewing often taxed the eyesight and dexterity of a seamstress and many of the examples I’ve shown used mind-bogglingly small stitches. They certainly boggled mine, anyway! Such microscopic work wasn’t limited to practical garments and household linen; it could also be used to make a sentimental token for someone special. The “watchpaper” above (which is obviously not paper) is an example.

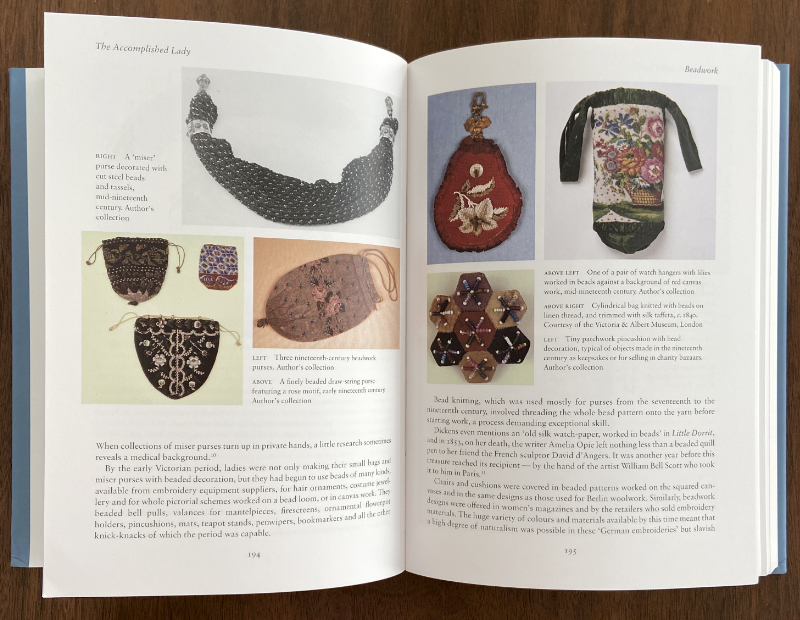

A watch was quite a luxury until the 18th century, but by the end of that era they were more common, although still greatly valued. It was customary to protect the delicate workings inside with little circles of paper that could be printed with a variety of pretty or amusing things such as portraits of famous people, landmarks, poetry, or even advertising for the maker. And of course, they gave ladies the perfect opportunity for artistic expression. Now highly collectible, some papers were painted, or perhaps inscribed with elegant calligraphy while others were… drumroll… made to show off needlework!

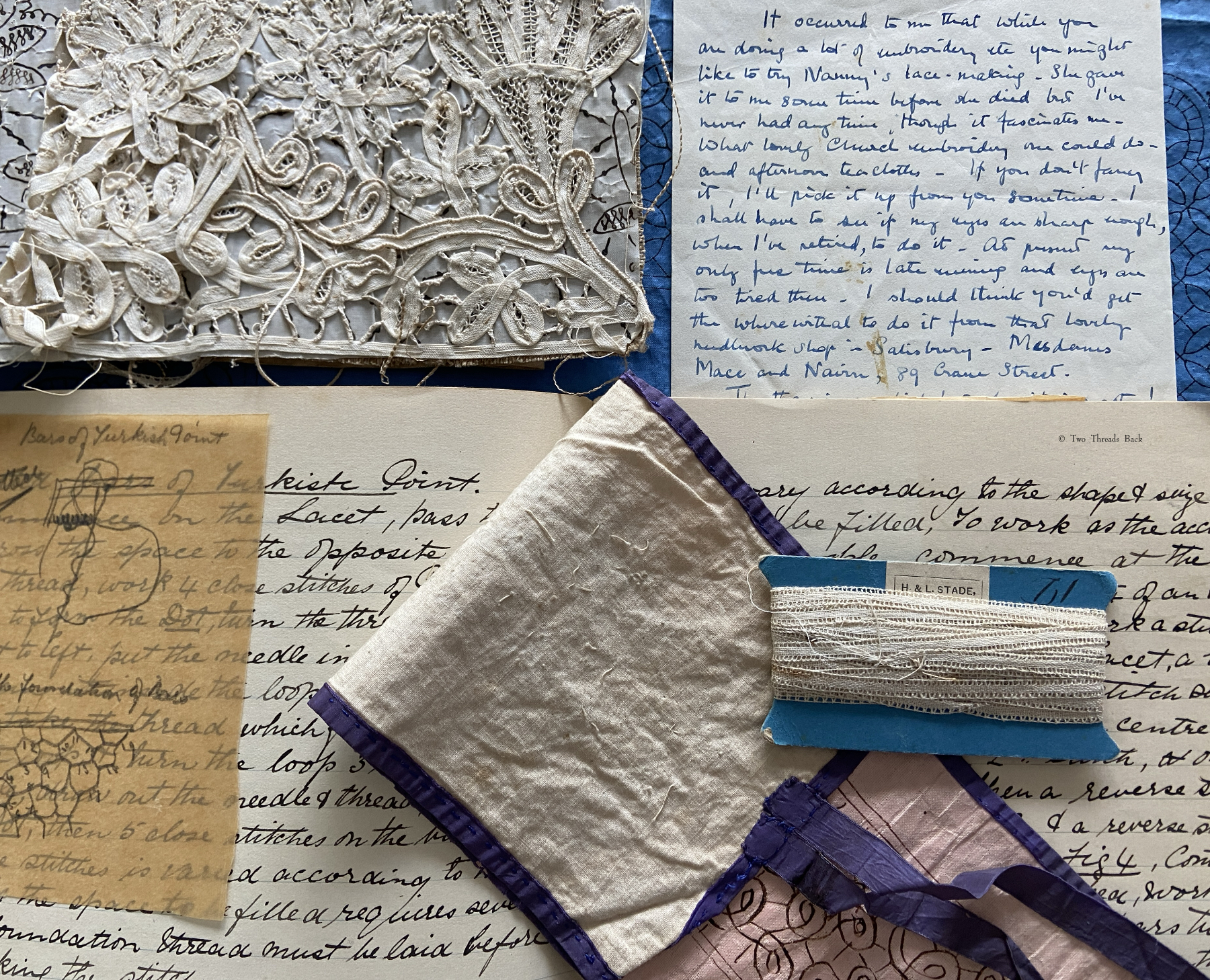

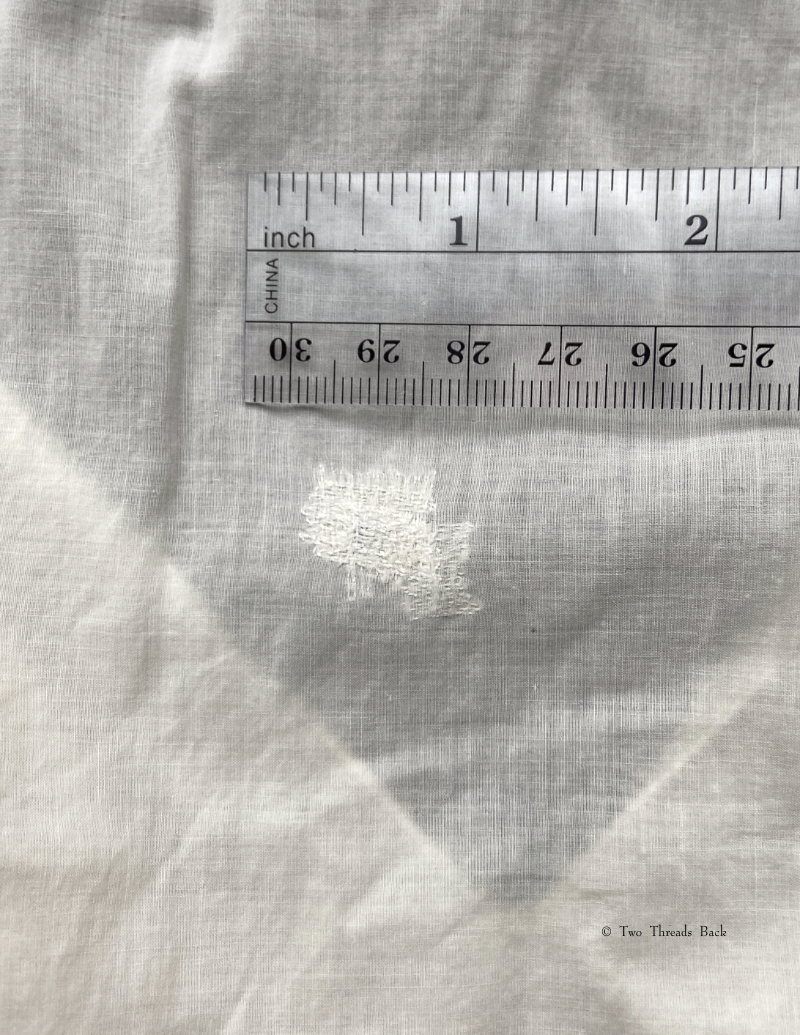

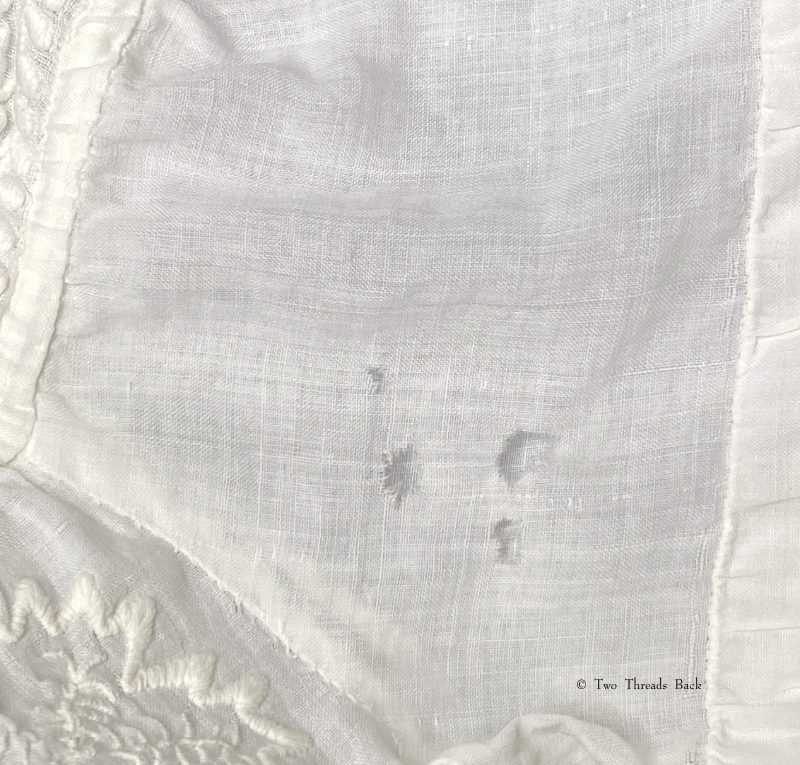

Watchpapers could be embroidered, made of lace, or use simple stitches such as cross-stitch (marking) to convey affection or good wishes. I’m not sure what kind has been used to make the one above since it’s so small and time has taken a toll. What I find most touching is that the maker who stitched

“With thee conversing I forget all time”

has woven the silk thread with her (?) his (?) hair for the embroidery! If you are a bit ambivalent about the “hairwork” or preserved locks found in old jewelry or albums, I understand. But I think the eeriness is part of its appeal, a personal touch through time that makes the past real.

I like the idea of making one of these myself. It would be utterly useless since I haven’t got a watch for it. It would create eyestrain to the point of a headache. But it would only require scraps of material and a little bit of time – my kind of project!

PS You’ll find more on the history of these tiny treasures online, and lots of pretty ones to see (Pinterest or auction sites) if they catch your fancy. PPS This one will be available on my Etsy site soon, as I continue uncollecting!