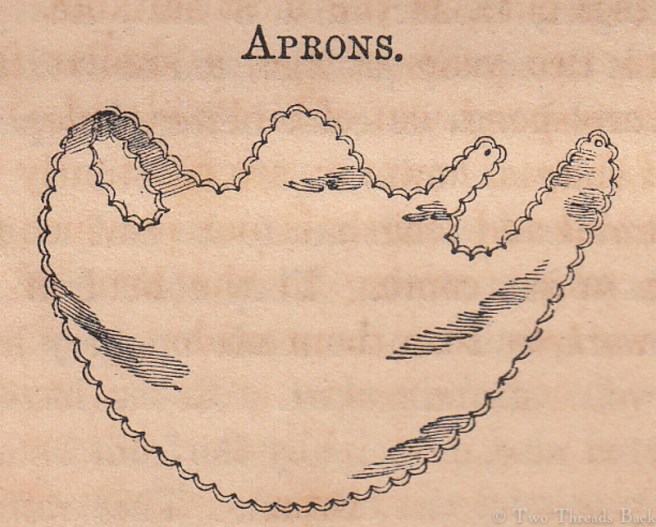

At three months old, it is usual to commence the use of aprons, which are made of bird’s-eye diaper, or, just now, brilliante, a firm, close-figured cambric, which will wear nearly as long. These last are bound with cambric, in solid colors, as pink, blue, buff, &tc. Bird’s-eye linen is usually trimmed with tatting or anything that wears well. At present, button-hole scollops, either plain or filled with dots, eyelets, &tc., are much used; they are made in this way ornamental, as well as useful. For an infant, the “bib-apron,” round front, coming a little below the waist, with a little shoulder strap buttoning around the arm (see cut), is the most suitable. From six months to two years of age, a similar front, with back to correspond, cut of bird’s-eye also. A large variety of shapes, however, are constantly to be had. The material and length is our province; no child needs an apron coming to the end of the dress skirt, as we have seen them made.

So says Sarah Hale, in a little instruction book written for new mothers in 1854. It amazes me that such a functional item could survive 150 plus years, but I come across them from time to time. If you’d like an actual-size pattern of the one below, send an email to me, m at twothreadsback dot com, and I’ll send you a pdf – free. Gratis. No strings attached!

The hems are almost invisible, so I assume Mother was able to use both hands for that. The tiny buttons are made of delicately carved mother of pearl.

Another common pattern, made for an older child, is like the one pictured below. It’s also made of diaper – but in linen – and trimmed at the armscyes and hem.