Patchwork quilting has earned a lofty place among the textile arts today, but 200 years ago a few writers felt inclined to poke fun at it. I was happily following rabbit trails, chasing plain sewing nuggets, when I came across some entertaining words on patchwork. A sketch written in 1821 found fault with the work AND the worker:

PATCH-WORK.

I have an old female cousin, who has passed a quarter of a century in rags, or rather amidst patches, destined to a most marvellous arrangement, for the furniture of a suite of apartments–a saloon, a boudoir, and a bed chamber. She began her paltry collection by begging of all her acquaintance, and wearing out every one by messages, notes, and applications for odd bits and patterns [i.e., printed fabrics].

She also told two score of lies, in order to obtain samples of different linen-drapers, but upon a very unwelcome observation of mine, she changed her operations.

Asking me one day if I did not think that the window curtains, ottomans, sopha-covers, et cætera, of her bow-windowed saloon would have a very novel, tasteful, and fantastic appearance, if composed of patch work judiciously arranged and bordered by a vandyke pattern worked by herself? I replied, “that the best patch-work which I ever saw had but a beggarly appearance, and that it would take her half her life, and lose her half her acquaintance, to collect the materials; that I always looked upon a patch-work curtain, or quilt to be fit only for a servant’s bed at an inn; that it was a complete make-shift, nay, that if she would make shifts for herself, or for the poor, she would be much more laudably employed. For I consider this patch-working something like lady-shoemaker’s work, below the dignity of the performer, and of little use when done.

All my observations would inevitably have been disregarded, for my cousin Cassandra is like many other old maids–she constantly asks advice with a predetermination to take her own way, but the term beggarly hurt her pride, and the thought of loss of company, to one who could not live without a morning gossip, and an evening casino, was very alarming; so she determined on buying remnants and small pieces of a thousand patterns; and in the long period above mentioned, she completed her patch-work hangings and furniture, which every one praised before her face, and treated with contempt behind her back. This chef-d’oeuvre of useless toil, was, however, shown to all her acquaintance, and furnished the subject of a hundred morning and tea-table conversations. –The Hermit in London, 1821

Well, that was pretty harsh! And I daresay a few million quilters today would agree. I’d rather he’d directed the fun toward installation art, but oddly enough it wasn’t around then. Satire could be brutal back in those insensitive days, and of course anything that hinted of vulgarity (patches!) was fair game. Knowing that the author was writing to entertain made me think perhaps it was a one-off, and the prevailing attitude was more favorable.

However, Lydia Maria Child (not one for tepid opinions), author of the Girl’s Own Book, was rather condescending as well when she said “we do not want young ladies to emulate their grandmothers in making patch-work quilts, or covering their apartments with hexagon- or octagon-starred carpets,” although in an earlier edition she admitted it to be a tolerable alternative to boredom:

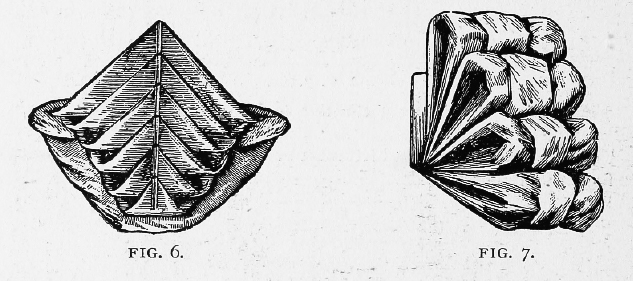

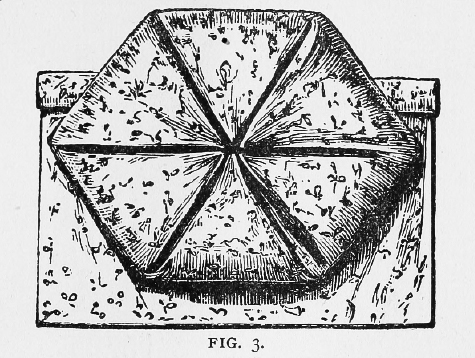

PATCH-WORK. This is old-fashioned too; and I must allow it is very silly to tear up large pieces of cloth, for the sake of sewing them together again. But little girls often have a great many small bits of cloth, and large remnants of time, which they don’t know what to do with; and I think it is better for them to make cradle-quilts for their dolls, or their baby brothers, than to be standing round, wishing they had something to do. The pieces are arranged in a great variety of forms; squares, diamonds, stars, blocks, octagon pieces placed in circles, &c. A little girl should examine whatever kind she wishes to imitate, and cut a paper pattern, with great care and exactness. –The Girl’s Own Book, 1833

Perhaps she had a point about tearing cloth just to sew it back together! But to balance out the disparaging remarks, I found a sweet essay about a patchwork quilt written in 1845 –and it mentions PLAIN SEWING! True, the author ranks a beloved patchwork quilt below a snowy counterpane, but the following excerpt glows with the warmest nostalgia. (Other textile historians have referenced it, but here’s a link to the original if you’d like to read the whole piece without my edits for brevity.)

THE PATCHWORK QUILT.

There it is! in the inner sanctum of my “old-maid’s hall”–as cosy a little room as any lady need wish to see attached to her boudoir….

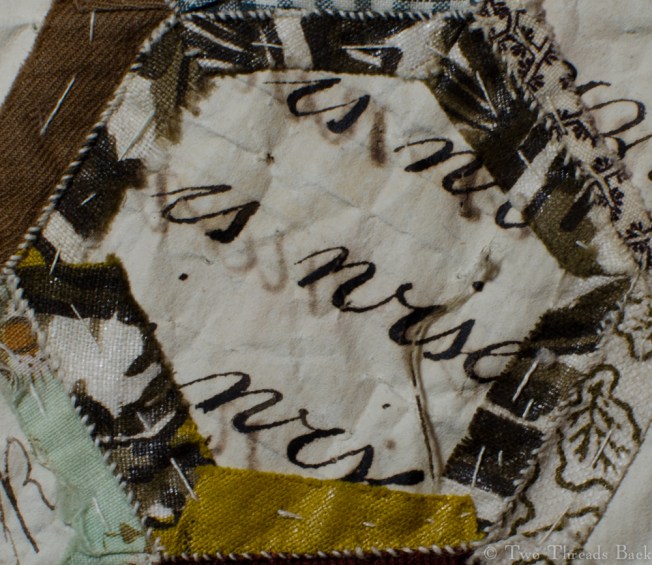

Yes, there is the Patchwork Quilt! looking to the uninterested observer like a miscellaneous collection of odd bits and ends of calico, but to me it is a precious reliquary of past treasures…. Gentle Friends! it contains a piece of each of my childhood’s calico gowns, and of my mother’s and sisters’; and that is not all.

I learned of the world’s generosity in rewarding the efforts of the industrious and enterprising…. What predictions that I should be a noted sempstress; that I should soon be able to make shirts for my father, sheets for my mother…. What legends were told me of little girls who had learned patchwork at three years of age, and could put a shirt together at six. What magical words were gusset, felling, button-hole stitch, and so forth, each a Sesame, opening into an arcana of workmanship… and a host of magical beauties!

Here is a piece of the first dress I ever saw, cut with what were called “mutton-leg” sleeves. Here, too, is a remnant of the first “bishop sleeve” my mother wore; and here is a fragment of the first gown that was ever cut for me with a bodice waist… and, oh, down in this corner a piece of that in which I first felt myself a woman- that is, when I first discarded pantalettes.

Here is a fragment of the beautiful gingham of which I had so scanty a pattern, and thus taxed my dress-maker’s wits; and here a piece of that of which mother and all my sisters had one with me. Here is a piece of that mourning dress in which I thought my mother looked so graceful; and here one of that which should have been warranted “not to wash,” or to wash all white. Here is a fragment of the pink apron which was pointed all around. Here is a token of kindness in the shape of a square of the old brocade-looking calico, presented by a venerable friend; and here a piece given by the naughty little girl with whom I broke friendship, and then wished to take it out of its place…. Here is a fragment of the first dress which baby brother wore when he left off long clothes; and here are relics of the long clothes themselves. Here a piece of that pink gingham frock so splendidly decked with pearl buttons. Here is a piece of that calico which so admirably imitated vesting, economical, bought to make “waistcoats” for the boys. Here are pieces of that to set off my quilt with, and bought strips of it by the cent’s worth – strips more in accordance with the good dealer’s benevolence than her usual price for the calico. Here is a piece of the first dress which was earned by my own exertions! And here are patterns presented by kind friends, and illustrative of their tastes.

Then there was another era in the history of my quilt. My sister–three years younger than myself–was in want of patchwork, while mine lay undisturbed. Yes, she was to be married; and I not spoken for! I gave her the patchwork.

Then came the quilting, a party not soon to be forgotten, with its jokes and merriment. Here is the memento of a mischievous brother, who was determined to assist otherwise than rolling up the quilt as it was finished, snapping the chalk-line, passing thread, wax and scissors, and shaking hands across the quilt for all girls with short arms. He must take the needle and thread. Well, we gave him white thread, and appointed him to a very dark piece of calico, so that we might pick it out the easier; but to spite us, he did it so nicely that it still remains, a memento of his skill with the needle.

And why did the young bride exchange her snowy counterpane for the patchwork quilt? These dark stains at the top of it will tell–stains left by the night medicines, taken in silence and darkness. The patchwork quilt rose and fell with the heavings of her breast as she sighed over the departing joys of life. Through the bridal chamber rang the knell-like cough which told us that we must prepare her for an early grave. The patchwork quilt shrouded her wasted form as she sweetly resigned herself to the arms of Death.

And back to me, with all its memories of childhood, youth, and maturer years; its associations of joy, and sorrow; of smiles and tears; of life and death, has returned to me The Patchwork Quilt. The Lowell Offering, 1845

Did you notice the reference to plain sewing? And making shirts? She’s singing my favorite song! An “arcana of workmanship.” Now there’s a title for a future post. Of course I don’t really think most people disparaged patchwork. There are too many survivors that show just how artistic, skillfully worked, and beloved pieced fabric was. I probably admire it more than most because I have no “pattern sense,” I can’t work with measures, shapes, design layout without a mental meltdown.

I’m happy simply to share the sentiments of the “Old Maid” above whose patchwork looked

to the uninterested observer like a miscellaneous collection of odd bits and ends of calico, but to me it is a precious reliquary of past treasures; a storehouse of valuables, almost destitute of intrinsic worth; a herbarium of withered flowers; a bound volume of hieroglyphics, each of which is a key to some painful or pleasant remembrance, a symbol of—but, ah, I am poetizing and spiritualizing over my ” patchwork quilt.”